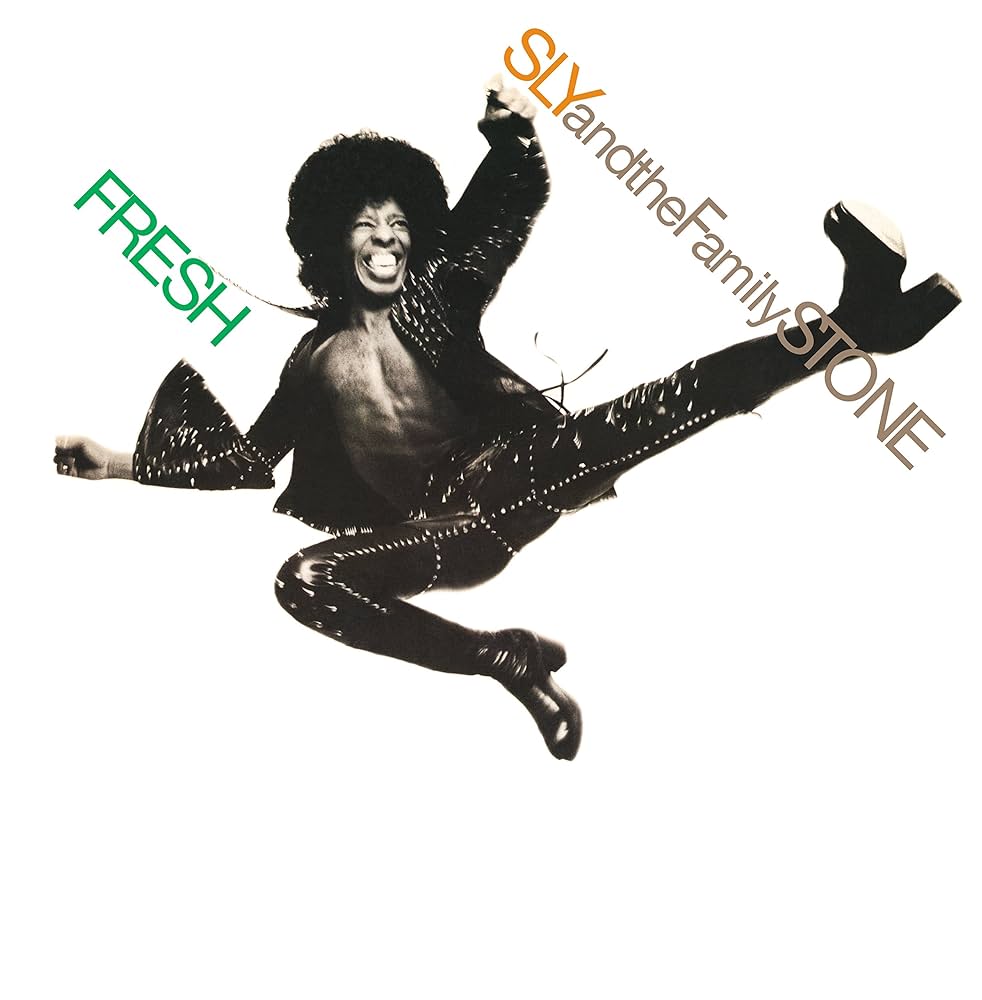

My album this week is the 1973 classic by funk and psychedelic soul pioneers Sly & The Family Stone – Fresh. A should be staple in any funk-lovers library, I think this is Sly Stone and his band at their peak – despite the challenging context in which it was born.

With this album (more than most I choose to discuss on Waxing Lyrical), I think the context surrounding Fresh is vital to understanding its sound, soul, and why it’s so significant.

Following modest success with their first three albums, the end of the 1960s was when Sly & The Family Stone’s trajectory truly began to soar; the now classic Everyday People 1968 was the group’s first Number 1, in 1968, and the track was the lead single for the band’s fourth album, Stand, released in 1969.

In the same year, the group headlined the Harlem Cultural Festival, and played slots at Newport Jazz Festival and the legendary Woodstock. This marked newfound heights for Sly & The Family Stone. With it, however, came significant internal issues. Towards the end of 1969, Sly Stone and his band members shifted their focus from musical output to heavy drug use, causing internal friction, turmoil, and the release of just one single in two years. This period also saw the departure of drummer Greg Erico.

Returning with monumental album There’s a Riot Goin’ On in 1971, a new era for Sly & The Family Stone was born, and it brought with it a darker sound: more experimental, gritty and representative of Sly’s experiences and feelings of hopelessness and despair. There’s a Riot Goin’ On is the predecessor to our Album of the Week.

By the time Fresh was released in 1973, Sly & The Family Stone had undergone significant line-up changes. Bassist Larry Graham had explosively left in 1972 (after supposedly having hired a hit man to take out Sly Stone), which, alongside the earlier loss of Erico, meant that the complete original rhythm section had departed.

Fresh was yet another development to Sly Stone’s sound; it’s more complex than the group’s earlier output, yet a little lighter and more accessible than its immediate predecessor. It relies heavily on drum machines, and, for me, is the peak of Sly Stone’s creativity.

Supposedly, opening track In Time was so admired by Miles Davis that he made his band listen to it on repeat for half an hour; if impressing one of the world’s greatest ever jazz musicians isn’t enough to make you want to listen to this record, then I don’t know what is.

If You Want Me To Stay is an absolute all-timer of a track. A simple but groovy bassline holds it down perfectly, and syncopated backings, solos and vocals contribute to the album’s most popular track – and rightly so.

Another of my highlights is the gospel-led, organ-filled cover of Que Sera, Sera, highlighting the voices of the Stones. It is beautifully infused with a rich funk and soul essence, and, interestingly, is also the only track on the album with Larry Graham credited on bass.

Fresh is one of those albums which has received more and more critical acclaim the longer it has been released. Initially received to another lukewarm reception, it’s now regarded as a classic, with plenty of awards, accolades, and mentions in lists declaring the greatest albums of all time.

Sly & The Family Stone wouldn’t make it much past further Fresh. Their final album as a group was released the following year, to poor sales, and the band gained an erratic and unreliable reputation in the live scene. Fresh is a landmark in not only Sly & The Family Stone’s musical history, but also the history of jazz, funk and soul, and the art of ‘funk-rock’. It was an album full of recording and production risks, influenced by hardship, and painstakingly laboured over by Sly Stone. And as a result, it’s one of the bet funk albums to ever be produced.